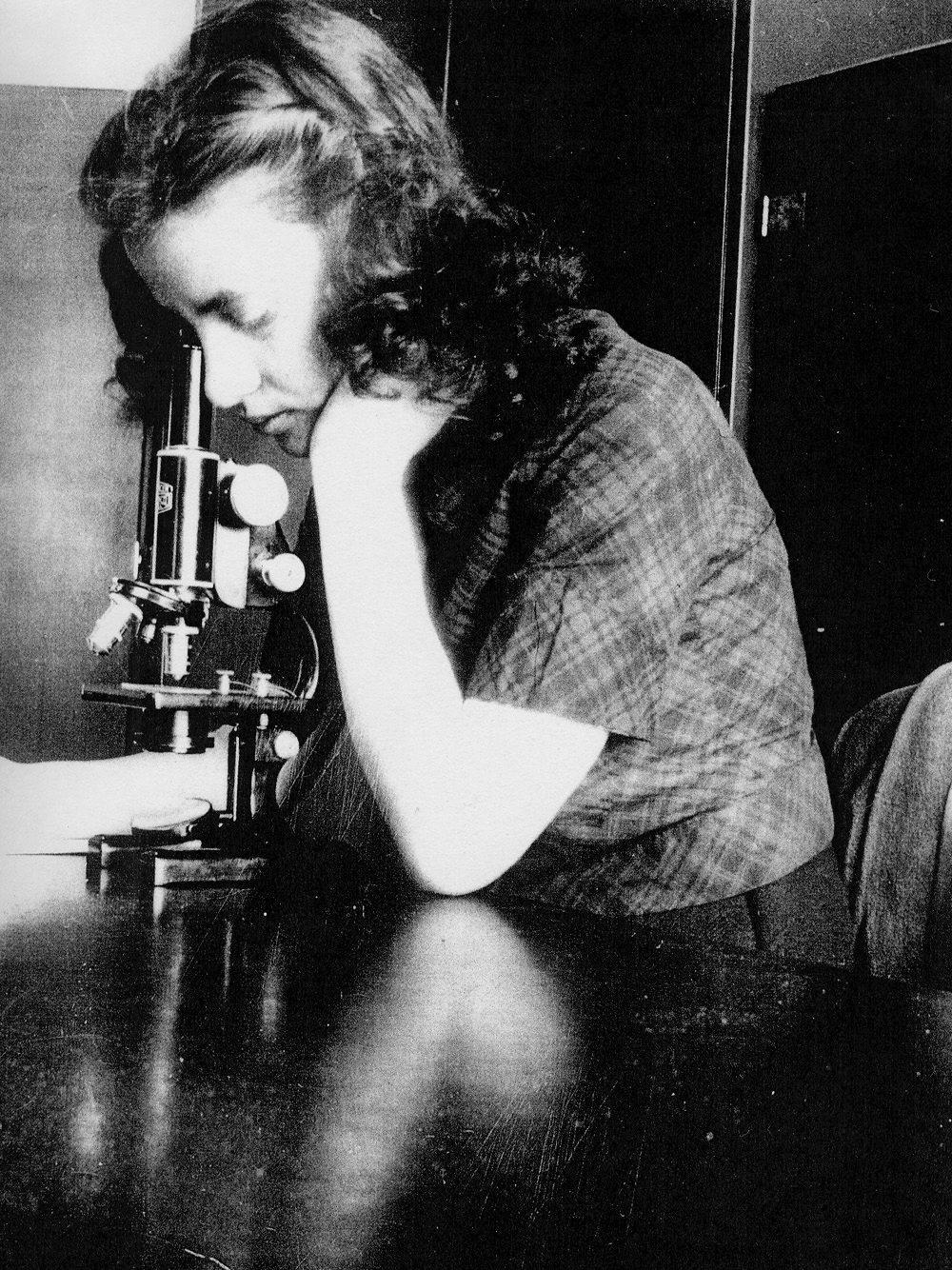

Esther Lederberg

So, who was Esther Lederberg and why is our project named after her? Continue reading and we will give you a short historical background about this amazing woman.

Esther Lederberg was born to an orthodox Jewish family during the great depression. Due to the recession, her school lunch often consisted of a piece of bread and tomato juice. Despite this, she thrived academically and chose to study biochemistry — against the advice of her teachers, who didn't see any future for women in that field. After completing her undergraduate degree at Hunter College in 1942, she was awarded a fellowship at Stanford University. Even here, she had trouble to get proper meals due to money struggles. Sometimes money was so tight that she recalled having to eat frogs' legs leftover from laboratory dissections. 1

In 1946 she received her master's degree at Stanford University in genetics, and the same year, she married a professor from the University of Wisconsin, Joshua Lederberg. In 1947, she joined her husband's research team as an unpaid research assistant at the University of Wisconsin. In 1950 she completed her doctorate. Esther stayed at the University of Wisconsin with her husband for the most 1950s, and this is where she discovered the lambda phage, the first temperate phage to be found! Her 1950 lambda phage paper led to an understanding of specialized transduction, and much of her work paved the way for future genetics research. 2

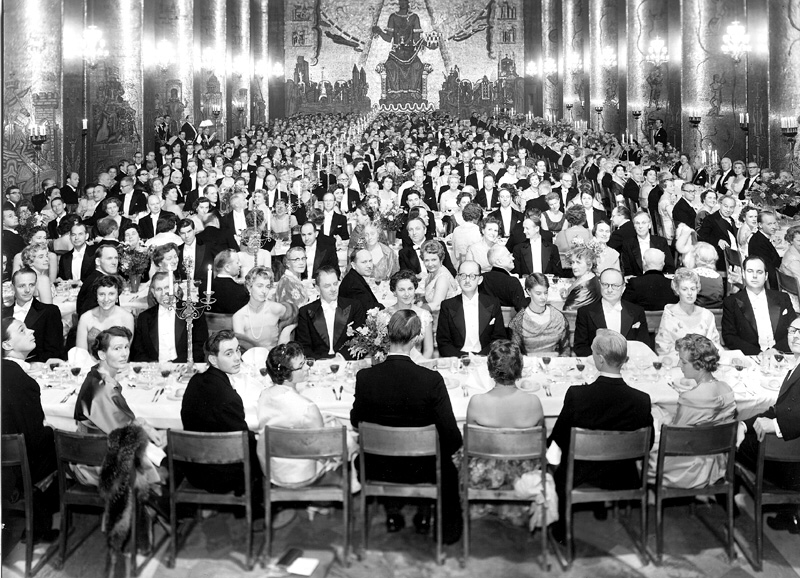

During her fellowship at Stanford, she was a research assistant to George W. Beadle and Edward Tatum, two geneticists. In 1958, George W. Beadle and Edward Tatum both won the Nobel Prize for discovering the role of genes in regulating biochemical events in cells. The same year, Joshua Lederberg also won the Nobel Prize for discovering that bacteria can mate and exchange genes. All of these discoveries wouldn’t have been possible without Esther’s work. Esther was present at the Nobel Prize ceremony in our hometown Stockholm. However, she was neither invited as a bacterial geneticist nor for her work, but as a wife of one of the men receiving the Nobel Prize. 2

In 1959 Esther moved back to Stanford University with her husband, Joshua. After having to petition the dean of Stanford over the lack of women professors at the school, she finally was appointed a position as a research associate on the basis that she accepted an untenured post. She was very much overqualified for the job. After 15 years, Stanford changed her title from Senior Scientist to Adjunct Professor. However, this did not give her tenure, and her contract was renewed only on a rolling basis (dependent on if she managed to get research grants or not). In 1976 she became the director of Stanford's plasmid reference center, and she continued as the center curator until 1986. 1

Esther helped discover a lot. Not only did this remarkable woman discover temperate phages, but she also found the F- fertile factor, a plasmid that allows for bacterial conjugation - this is, the transfer of genetic material between two bacteria through direct contact, and not through a phage, which is the case of transduction. Furthermore, she also designed a technique to screen multiple bacteria phenotypes through different conditions, called replica plating.

She did not get the recognition she deserved throughout her life, and our project would not be possible without her research, and so we dedicate our work to her, and to all women in science!

References

- https://www.whatisbiotechnology.org/index.php/people/summary/Lederberg_Esther

- https://time.com/longform/esther-lederberg/

Images from the Esther M. Zimmer Lederberg memorial website.