Design

Designing an herbicide-tolerant rhizobium

Herbicide selection:

Various pesticides have been shown to inhibit nitrogenase activity in soil bacteria (both symbiotic and free-living) (Fox et al., 2007). This effect limits the availability of usable nitrogen for plants which requires farmers to supplement their crops with nitrogen fertilizers (Fox et al., 2007). However, nitrogen fertilizers cause nutrient pollution and contaminate water-ways leading to algal blooms and ecological damage (Heisler et al., 2008).

The goal of this project is to provide a solution in which rhizobia (legume root symbionts) contain pesticide metabolic genes to generate root nodules and exhibit nitrogenase activity in the presence of pesticides. This would limit the need for nitrogen rich fertilizers and lower pollution caused by both fertilizers.

Thus, a target pesticide for this project would be able to be degraded or biotransformed to less toxic products that can be more readily degraded by common soil microflora. Additionally, a pesticide of interest would be one that is used prominently in Canada, specifically in the regions of southern ontario. Lastly, for the symbiotic rhizobia to form symbiotic relationships with the plant, the pesticide must be applied to a leguminous crop.

Linuron was identified as an herbicide that fits all three criteria since literature has identified some genes and metabolic pathways involved in the degradation or transformation of linuron (xenobiotic phenylurea pesticide). These genes are further described below in ‘choosing the genes’. It is also an herbicide used in Canada and is of particular interest as its use is currently in the process of being re-evaluated by Health Canada (Health Canada, 2012). This herbicide is used to control broadleaf and grassy weeds prior to planting and is used as a staple ingredient in many herbicide applications for Canadian growers (Health Canada, 2012). Lastly, linuron in North America is used for the treatment of tubers and legumes including soybean plants which are capable of forming root nodules with various rhizobia species (Health Canada, 2012).

Plant selection:

As above, for increased root nodule formation and symbiotic nitrogen fixation in the presence of linuron, the plant chosen must also satisfy certain criteria. These included use in Canada/Southern Ontario, being a crop onto which linuron is applied, and capacity to form root nodules with rhizobia. The soybean plant was chosen as it satisfies these criteria by (1) comprising 2 million acres of crop land in Ontario, (2) being a known crop to which linuron is applied to as a pre-emergence herbicide, and (3) being able to form root nodules with certain species of rhizobia such as Rhizhobia fredii, Bradyrhizobium Diazoefficiens, and Bradyrhizobium elkanii (OMAFRA, 2018 and Farm Journal AgPro, 2014).

Furthermore, although soybean is not quite a model organism, it is well-studied due to its agricultural importance (Pitzschke, 2013). It also germinates, grows, and shows evidence of root nodulation relatively quickly compared to other crops to which linuron is applied (Pitzschke, 2013). Thus, by using soybeans as a plant symbiont for rhizobia, nodulation in the presence of pesticide could be directly assayed through nodule counts.

Rhizobium selection:

Once soybean was selected as the target plant, the choice of bacteria was limited to three rhizobia species, Rhizhobia fredii, Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens, and Bradyrhizobium elkanii (Farm Journal AgPro, 2014). From these three, Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens USDA110 was selected in part because it is also well-studied (with literature including that done under the species’ former name Bradyrhizobium japonicum). It is also used in commercial rhizobia inoculants for soils designed to improve the nitrogen fixation yield of soybean crops (Prevost & Bromfield, 2003). Despite its slow growth (several days are required to get visible growth), Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens USDA110 was chosen for this project due to its prevalent use as an inoculant in Ontarian soils (Prevost & Bromfield, 2003).

DNA design:

Vector selection:

For assembly of the system to be used in both E. coli for construction and Bradyrhizobium Diazoefficiens, the plasmid pRJPaph was used. Different versions of this plasmid encode a variety of fluorescence or enzymatic reporters (Ledermann et al., 2015). We chose to use the pRJPaph-mCHERRY and pRJPaph-GFP fluorescent reporter versions of the plasmid for our project as we could easily measure fluoresence with our lab equipment. We decided to use the GFP plasmid for further cloning (to insert degradation genes) to create the engineered strains. mCherry will act as an empty vector control in our later experiments.

These plasmids were designed for stable integration into the B. diazoefficiens genome (Ledermann et al., 2015). We could edit them and complete our construction in E. coli and then conjugate the plasmids into B. diazoefficiens. The plasmids integrate into the B. diazoefficiens genome, downstream of the of the scoI gene, without affecting the bacteria's ability to form root nodules (Ledermann et al., 2015).

The degradation genes:

Linuron is a chlorinated urea-based herbicide, and despite being a synthetic herbicide - a xenobiotic that is foreign to ecological systems - quite a few degradation/biotransformation pathways have been identified (Stoker & Kavlock, 2010). These pathways and associated genes were identified through a thorough literature search.

For some of these pathways the genes required are not yet fully identified. For others, the gene segments are identified but riddled with other functional DNA sequences that make identification of the aspects required and controlled engineering difficult. Additionally, in each case, the goal is to either fully mineralize linuron or end-up with a product less toxic than linuron itself and other naturally occurring degradation products. Therefore, the final genes chosen represent a biotransformation pathway that takes elements from several different sources.

The aim of the project was to confer an increased tolerance, if not a resistance, to linuron in our engineered rhizobia. There are a multitude of evolutionary distinct pathways that could be utilized - but the final genes selected belonged to two different pathways that are not known to be associated.

The advantages and disadvantages brought on by all found pathways and degradation-related genes were taken into consideration when deciding upon the final pathway for this project. Below is a description of the chosen pathway, as well as those considered during our design process.

Chosen Pathway: nat1 and libA

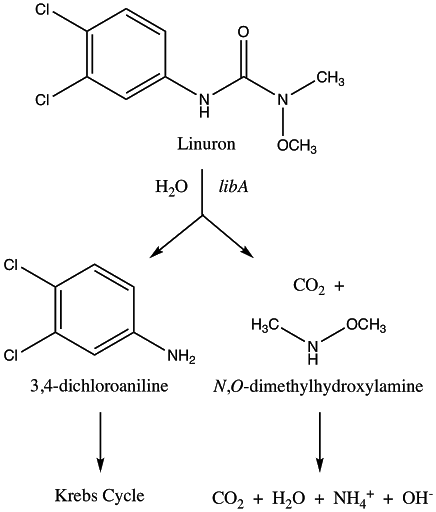

In this case, linuron is not fully degraded but instead is biotransformed to N-acetyl-3,4-Dichloroaniline (N-acetyl-3,4-DCA). This strategy is beneficial in that herbicide that is transformed into 3,4-Dichloroaniline (3,4-DCA) can be acetylated into a less toxic product (Dupret et al., 2011). In fact, the acetylated product is considered as a plausible endpoint for bioremediation of soil contaminated with the same class of herbicide as linuron (Dupret et al., 2011).

The first degradation step in this pathway is the conversion of linuron to 3,4-DCA by libA. LibA is a linuron hydrolase with activity specific to linuron (it lacks activity towards other phenylurea herbicides tested) (Bers et al., 2011). It was originally identified in Variovorax sp. Strain SRS16 and has orthologues present in other tested linuron-degrading Variovorax strains (Bers et al., 2011). This step also leads to the production of the byproduct N,O-dimethylhydroxylamine (N,O-DMHA) (Bers et al., 2011). However, while DCA is toxic and resistant to decomposition, N,O-DMHA is not harmful and is easily degraded (Bers et al., 2011). Therefore, while N,O-DMHA does not need any additional processing steps, 3,4-DCA necessitates additional transformation before a non-toxic product can be yielded (Bers et al., 2011).

The second degradation step is the conversion of 3,4-DCA to N-acetyl-3,4-DCA by nat1. Nat1 is an arylamine N-acetyltransferase (NAT) (Rodrigues-Lima et al., 2016). These are xenobiotic-metabolizing enzymes involved in detoxification, such as the detoxification of 3,4-DCA to N-acetyl-3,4-DCA (Rodrigues-Lima et al., 2016). The gene used for nat1 in this project was originally cloned from Mesorhizobium loti which is another root-nodule forming bacterium (Rodrigues-Lima et al., 2016). Nat1 was chosen from other NAT’s identified because it was shown to be much more effective at acetylating 3,4-DCA (ex: more than 136 times more effective than nat2) (Rodrigues-Lima et al., 2016). Additionally, the paper through which this gene was identified represents the first evidence for xenobiotic detoxification pathway via plant symbiosis with soil microorganisms, which forms the foundation for this project (Rodrigues-Lima et al., 2016). Again, this step is important since linuron is not the only toxic chemical, but accumulation of 3,4-DCA in the soil must be avoided which is solved through this transformation step (Rodrigues-Lima et al., 2016).

As a whole, this pathway benefits from being complete with well-documented genes and enzymatic processes. The selected genes aim to deter the accumulation of toxic and recalcitrant compounds by producing the non-harmful compounds N,O-DHMA and N-acetyl-3,4-DCA as a result of biotransformation of linuron.

However, because the presence of N-acetyl-3,4-DCA is difficult to assay, the experimental design to measure activity of nat1 and libA expression was two-pronged. The first aim was to identify effectiveness of nodulation by both the engineered and un-engineered rhizobia strains, in the presence of linuron, and without the herbicide present.

For this, soybean plants grown in facilities at the University of Waterloo by the iGEM team would be inoculated, by seed-coating or flooding techniques, and then allowed to grow for 3-4 weeks. Nodulation would be the major quantitative measure of effectiveness of the bacteria, using the dry weight of nodules for each plant as a measure. However, if there is a distinct increase in nitrogen fixation, it could potentially be seen reflected in plant growth.

The second approach would be to use end-point minimal inhibitory concentrations (MIC), to determine changes in tolerance between the engineered rhizobia and unengineered wild-type. This would not reflect their survival in soil environments, but would give an indication to the comparative effect of the herbicide on the two bacteria. If it is detected that the MICs increased for the engineered strain, it would indicate that the genes provided confer an increased tolerance to the herbicide or its tested derivatives.

Alternative pathway 1: full Mineralization

Microbial degradation is an important mechanism in the dissipation of linuron and other phenylurea herbicides in the environment. Therefore, the ideal goal would be to achieve full mineralization of the linuron as a substrate. With this in mind, linuron could be used as a substrate to sustain the growth of the bacteria (bacteria would grow on agar plates containing just linuron). This has been observed in Variovorax sp. Strain SRS16, which is able to fully mineralize linuron, and some genes involved in this metabolic pathway have already been identified (Bers et al., 2011). The mineralization is conducted through a pathway initiated by the hydrolysis of linuron to 3,4-DCA, by libA, which is then converted to Krebs cycle intermediates (Bers et al., 2011).

The entire pathway is shown below:

However, the dcaQTA1A2BR and ccdRCFDE gene clusters open reading frames (ORF) only been identified by their possible products and enzymatic function bioinformatically (Bers et al., 2011). Additionally, it is indicated that the dcaQTA1A2BR gene cluster is located within a transposon-like structure (Bers et al., 2011). Therefore, due to the complexity and time associated with identifying and experimentally validating the necessary ORF’s in house and working with a transposon-containing gene cluster, this pathway was not chosen (Bers et al., 2011). If further publications, show additional information on these gene clusters, this pathway could become an ideal solution later on as it leads to full mineralization.

If this pathway were to be used, an experimental method to determine the success of this strategy would be to grow Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens on agar containing linuron as the sole carbon source (Bers et al., 2011). Growth would indicate that the bacteria is successfully metabolizing linuron into Kreb’s cycle intermediates used for energy production.

Alternative pathway 2: The Nah Pathway

A second alternative pathway described by Kim et al. in 2015 was identified as the nahHIJKLMNO pathway. The genes in this pathway were all originally identified in Pseudomonas sp. KB35B. and the reading frame for each gene was well characterized. However, the first step in this pathway from 3,4-DCA to Catechol is catalyzed through unknown enzymatic means. Overall, this pathway was not chosen due to the major gap between 3,4-DCA and catechol (we could not find any other characterized enzymes in the literature that catalyze similar reactions), and its higher level of complexity compared to using just two genes as described previously.

The pathway is shown below:

Experimental Design

As mentioned throughout the description of the pathways, there are a few ways in which we envision testing our engineered system. These approaches include assaying the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of the engineered rhizoba in the presence of herbicide, assaying nodulation volume of individually inoculated plants, and competitive nodulation assays.

The focus was placed on these functional assays for the system since presence of N-acetyl-3,4-DCA and 3,4-DCA is difficult to assay without complex analytical chemistry techniques (Sandermann et al., 1998). Therefore the strategy was not necessarily to assay the specific activity of LibA and Nat1, but instead to assay their success as a system in increasing herbicide tolerance and nodulation.

Lastly, there is still some uncertainty in the literature as to the exact mechanism through which nodulation and nitrogen fixation is decreased in the presence of linuron. The main possibilities are (1) that the rhizobia are not tolerant to the pesticide, (2) the chemical signaling of the symbiotic interaction between plant root and rhizobia is disrupted by linuron thus preventing nodulation, and (3) the herbicide is decreasing the rhizobia’s ability in the formed nodule to exhibit nitrogenase activity. The ability of our system to improve any of these rhizobial abilities were assayed by measuring MICs for (1), and conducting root nodulation assays for (2) and (3).

Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) Herbicide Tolerance Assays

We sought to use MIC experiments to evaluate the ability of our system to lend our organism increased linuron concentration.

MIC experiments evaluate the growth rate of microorganisms across a range of toxin concentrations, determining the minimum toxin concentration at which growth is inhibited. If LibA and NAT1 were successfully expressed in the right amounts, our engineered strain would convert linuron to 3,4-DCAA, allowing it to grow more quickly than the wild type at higher linuron concentrations.

In order to investigate our engineered system’s behaviour in detail, we chose to evaluate the toxicity of both linuron and 3,4-DCA. This would allow us to investigate the function of both LibA and NAT1. We chose to use wild-type bacteria, those containing the empty pRJPaph-GFP vector, and those containing the construct with LibA and NAT1. Given the potential for increased metabolic burden due to pRJPaph-GFP, we decided to evaluate the success of our system by comparing the tolerance of the empty vector and construct strains only.

Although the main goal was to evaluate our engineered B. diazoefficiens, we also chose to investigate the behaviour of E. coli. This is because E. coli is a convenient proxy for B. diazoefficiens due to its much faster growth rate. E. coli was also used to conduct our cloning. The pRJPaph plasmid is expressed in both E. coli and B. diazoefficiens (Ledermann et al., 2015).

Relevant starting ranges of linuron and 3,4-DCA concentrations to test were chosen based on existing literature for other microbial organisms. Linuron was reported to cause toxic effects at 74 µM (Santos, 2014), complete inhibition at 200 µM (Santos, 2014), and to inhibit root nodule formation at 12 µM (Fernandez-Pascual, 1988). 3,4-DCA was reported to cause toxic effects at 3 µM (Tixier, 2002). Our toxin concentration ranges were also limited by the relatively low water solubilities of linuron and 3,4-DCA: 301 µM and 568 µM respectively. We therefore chose to use linuron concentrations of 290 - 4.42E-02 µM and 3,4-DCA concentrations of 550 - 8.38E-02 µM.

The following cases describe what could be observed in the MIC results. All cases refer to the organism with the construct versus the empty vector. These are based on the assumption that the desired end product, 3,4-DCAA, is of limited toxicity, that 3,4-DCA is very toxic, and that linuron has an intermediate toxicity, as described by Tixier et al (Tixier, 2002).

1. If NAT1 is sucessfully expressed:

- The organism will show increased tolerance to 3,4-DCA due to NAT1's ability to transform 3,4-DCA into 3,4-DCAA, a less toxic derivative

2. If LibA is successfully expressed without NAT1:

- The organism’s 3,4-DCA tolerance will be unchanged

- The organism’s linuron tolerance will be lower since LibA will catalyse the formation of toxic 3,4-DCA, which cannot be further transformed

3. If LibA is successfully expressed in addition to NAT1:

- The organism may show higher or lower tolerance depending on the relative rates of the two reactions (3a, 3b)

3a. If NAT1 is working much faster than LibA:

- The organism will show higher tolerance to linuron

- Linuron is broken down to the more toxic 3,4-DCA by LibA, but the 3,4-DCA is quickly converted to the less harmful 3,4-DCAA so that the 3,4-DCA concentration never reaches toxic levels

3b. If NAT1 is working much slower than LibA:

- The organism will show lower tolerance to linuron

- Linuron is broken down to the more toxic 3,4-DCA by LibA, and 3,4-DCA accumulates in the cell since NAT1 is not able to break it down fast enough

- The accumulated 3,4-DCA causes toxic effects in the cell

Each of these cases is described in more detail with quantitative justification on our model page. Enzymatic reaction rate is proportional to both enzyme concentration and the kinetic parameter kcat, neither of which is well-characterised for our system.

Overall, the measurement and determination of MICs for the engineered and non-engineered rhizobia would allow us to determine if we have conferred a tolerance to linuron with our genetic system.

Root-Nodulation Assays

Root nodulation assays would be used to directly measure the ability of the engineered rhizobia to nodulate soybean plants in the presence of linuron. Whereas the mass/size of nodules has shown to be directly related to nitrogen fixation ability (Tajima et al., 2007).

For these assays, soybean plants grown in the facilities at the University of Waterloo would be individually inoculated using either see-coating or flooding techniques (described in the Experiments page). Allowing 3-4 weeks of growth would ensure the nodules have been given sufficient time to form. During this time, the herbicide would be applied according to typical use protocols/recommended guidelines for the chosen herbicide. Finally, the nodules would be assayed for dry weight, individual size, and colorimetrically (with the fluorescent reporter genes).

Dry weight of soybean plants inoculated with an empty vector control of the B. Diazoefficiens can be compared to dry weight of rhizobia containing the herbicide degradation pathway. This would be done by manually extracting the nodules from the roots of the plants, drying, and weighing.

The size of the extracted nodules can also be used to link to nitrogenase activity (Tajima et al., 2007). Where larger nodules correspond to more nitrogen fixation, and smaller nodules are less active in nitrogen fixation (Tajima et al., 2007). Thus, before drying and massing nodule weight, the nodule diameter can be measured and the average nodule size for each soybean (with degradation genes vs. without) could be linked to better nitrogen fixation.

Lastly, a competitive nodulation assay could be used to determine if the engineered rhizobia would outcompete the empty vector strain in colonizing soybeans. This would help us determine if our engineered strain could compete with non-engineered rhizobia that would be naturally found in fields (if this were to be applied in real life). This test would involve inoculating one soybean plant with equal amounts of (1) B. diazoefficiens with an empty vector with an mCHERRY reporter and (2) B. diazoefficiens with the libA and nat1 genes with a GFP reporter. After waiting for nodulation, the amount of red (mCHERRY containing) nodules compared to green (GFP+libA+Nat1 containing) nodules would be counted. If more green nodules were observed this would indicate that the libA and nat1 conferred to the rhizobia increased abilities to nodulate in the presence of linuron.

Additional herbicide:

While the literature indicated that the transformation of linuron and 3,4-dichloroaniline into 3,4-dichloroacetanilide should reduce the toxicity of the bacteria’s environment, there were still many unknowns at this stage of the project design such as the relative kinetics of these two enzymatic transformations and whether the partial degradation of linuron would be sufficient. As such, we wanted to design another herbicide tolerance system using a more well-studied herbicide.

We found that the commonly-used glyphosate herbicide also inhibited nitrogen fixation in root nodules (Zablotowicz & Reddy, 2004). We also found a relatively simple pathway for the degradation of glyphosate to metabolic intermediates by C-P lyase and sarcosine oxidase (Grandcoin et al., 2017). However, we decided to engineer glyphosate tolerance via a different mechanism.

Glyphosate is typically utilized with “Round-Up Ready” plants by Monsanto which have been genetically engineered to be resistant to the pesticide. This was accomplished by replacing the wild type copy of the enzyme inhibited by glyphosate, 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate (EPSP) synthase, with a copy of the gene found in agrobacterium sp. strain CP4, which demonstrates low levels of inhibition. When this glyphosate-resistant gene is engineered into soybeans, the shikimate pathway, which is required for the production of aromatic amino acids, is no longer inhibited and the plant is able to survive (Funke et al., 2006). We envisioned that by integrating this CP4 EPSP synthase gene from the original Monsanto patent (which we codon optimized for B. diazoefficiens) into the genome of our rhizobia, we could introduce glyphosate tolerance, in the same way it is done for plants. We chose to pursue this project alongside our linuron project in hopes of demonstrating that rhizobia could be made tolerant to different herbicides by a variety of ways and that mechanisms to accomplish this could be tailored to each herbicide.

Optimizing Growth Conditions for Soybeans

The optimization of growth conditions for the soybeans was conducted by growing the soybean seeds in different set-ups, testing different conditions for germination, and using different watering schedules.

The growth conditions that remained constant throughout the experiments were temperature, photoperiod, and light intensity. These conditions were provided by Scott Liddycoat, a technician in the Department of Biology at the University of Waterloo. He was frequently consulted, and provided advice on watering conditions for the soybeans to facilitate nodulation. Scott supplied the growth cabinet conditions used at the University of Waterloo for growing soybeans. It was decided that the normal conditions for temperature, photoperiod and light would be sufficient for the experiments, and that they did not require conditions that deviate from what is typically seen in literature (Lebreton, Labbé, De Ronne et al, 2018; Schweitzer & Harper, 1980). A condition that was not measured or controlled was the humidity inside the growth cabinet.

The watering schedule was the only thing subject to change; in all instances DI-water was used, as to further starve the plants of nutrients, encouraging nodulation. Vermiculite was soaked, watered by flooding for fifteen minutes, and applied topically by a watering can. The topical application showed the best results, despite being the least quantitative measure of watering. Soaking and flooding the vermiculite resulted in soybeans with stunted growth.

Since the plants were not grown past a period of four weeks, it was not deemed necessary supply the soybeans with any fertilizer. This should have also further encouraged root nodule formation through nutrient deprivation. Vermiculite was used for this reason as well - it is easier to control which nutrients are in vermiculite, rather than soil.

The growth portion of the experiments was conducted non-aseptically due to available equipment, available space and little risk of contamination from microorganisms that would compromise the results of the experiments.

The final growth conditions were:

- Cabinet settings of 16 hours of high light at 21°C and 8 hours of no light at 19°C

- Topical application of DI water as needed

- Germinated seeds added to pots of soaked vermiculite

References:

Bers, K., Leroy, B., Breugelmans, P., Albers, P., Lavigne, R., Sørensen, S. R., … Springael, D. (2011). A Novel Hydrolase Identified by Genomic-Proteomic Analysis of Phenylurea Herbicide Mineralization by Variovorax sp. Strain SRS16. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 77(24), 8754–8764. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.06162-11

Dupret, J.-M., Dairou, J., Busi, F., Silar, P., Martins, M., Mougin, C., … Cocaig, A. (2011). Pesticide-Derived Aromatic Amines and Their Biotransformation. Pesticides in the Modern World - Pests Control and Pesticides Exposure and Toxicity Assessment. https://doi.org/10.5772/18279

Farm Journal AgPro. (2014, January 10). Attention Required! | Cloudflare. Retrieved October 19, 2019, from https://www.agprofessional.com/article/soybeans-and-rhizobia-mutually-beneficial-relationship

Fernandez-Pascual, M., Pozuelo, J., Serra, M., & De Felipe, M. (1988). Effects of cyanazine and linuron on chloroplast development, nodule activity and protein metabolism in lupinus albus L. Journal of Plant Physiology, 133(3), 288-294. doi:10.1016/S0176-1617(88)80202-5

Fox, J. E., Gulledge, J., Engelhaupt, E., Burow, M. E., & McLachlan, J. A. (2007). Pesticides reduce symbiotic efficiency of nitrogen-fixing rhizobia and host plants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(24), 10282–10287. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0611710104

Funke, T.; Han, H. Healy-Fried, M. L.; Fischer, M.; Schönbrunn, E. (2006). Molecular basis for the herbicide resistance of Roundup Ready crops. PNAS, 103(35), 13010-13015.

Grandcoin, A.; Piel, S.; Baurès, E. (2017). AminoMethylPhosphonic acid (AMPA) in natural waters: Its sources, behavior and environmental fate. Water Research, 117, 187-197.

Health Canada. (2012). Proposed Re-evaluation Decision PRVD2012-02, Linuron - Canada.ca. Retrieved October 19, 2019, from https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/consumer-product-safety/pesticides-pest-management/public/consultations/proposed-re-evaluation-decisions/2012/linuron.html

Heisler, J., Glibert, P. M., Burkholder, J. M., Anderson, D. M., Cochlan, W., Dennison, W. C., … Suddleson, M. (2008). Eutrophication and harmful algal blooms: A scientific consensus. Harmful Algae, 8(1), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hal.2008.08.006

Kim, Y.-M., Park, K., Kim, W., Shin, J., Kim, J., Park, H., & Rhee, I. (2007). Cloning and Characterization of a Catechol-Degrading Gene Cluster from 3,4-dichloroaniline Degrading Bacterium Pseudomonas sp. KB35B. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 55, 4722–4727.

Lebreton, A., Labbé, C., De Ronne, M., Xue, A. G., Marchand, G., & Bélanger, R. R. (2018). Development of a simple hydroponic assay to study vertical and horizontal resistance of soybean and pathotypes of Phytophthora sojae. Plant disease, 102(1), 114-123.doi: 10.1094/PDIS-04-17-0586-RE

Ledermann, R., Bartsch, I., Remus-Emsermann, M. N., Vorholt, J. A., & Fischer, H.-M. (2015). Stable Fluorescent and Enzymatic Tagging ofBradyrhizobium diazoefficiensto Analyze Host-Plant Infection and Colonization. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions, 28(9), 959–967. https://doi.org/10.1094/MPMI-03-15-0054-TA

Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food, and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA). (2018, February 8). Soybean Production in Ontario. Retrieved October 19, 2019, from http://www.omafra.gov.on.ca/english/crops/field/soybeans.html

Pitzschke, A. (2013). From Bench to Barn: Plant Model Research and its Applications in Agriculture. Advancements in Genetic Engineering, 02(02). https://doi.org/10.4172/2169-0111.1000110

Prévost and E. S P. Bromfield, D. (2003). Diversity of symbiotic rhizobia resident in Canadian soils. Canadian Journal of Soil Science, 83(Special Issue), 311–319. https://doi.org/10.4141/S01-066

Rodrigues-Lima, F., Dairou, J., Diaz, C. L., Rubio, M. C., Sim, E., Spaink, H. P., & Dupret, J.-M. (2006). Cloning, functional expression and characterization of Mesorhizobium loti arylamine N-acetyltransferases: rhizobial symbiosis supplies leguminous plants with the xenobiotic N-acetylation pathway. Molecular Microbiology, 60(2), 505–512. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05114.x Stoker, T. E., & Kavlock, R. J. (2010). Pesticides as Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals. Hayes’ Handbook of Pesticide Toxicology, 551–569. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-374367-1.00018-5

Sandermann, H., Heller, W., Hertkorn, N., Hoque, E., Pieper, D., & Winkler, R. (1998). A New Intermediate in the Mineralization of 3,4-Dichloroaniline by the White Rot Fungus Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 64(9), 3305–3312. Retrieved from https://aem.asm.org/content/64/9/3305

Santos, S., Romeu, V., Maria, F., Sharon, C., António, M., Joaqium, V., & Amália, J. (2014). Toxicity of the herbicide linuron as assessed by bacterial and mitochondrial model systems. Toxicology in Vitro, 28 doi:10.1016/j.tiv.2014.04.004

Schweitzer, L. E. & Harper, J. E. (1980). Effect of Light, Dark and Temperature on Root Nodule Activity (Acetylene Reduction) of Soybeans. Plant Physiology, 65(1), 51-56. doi: 10.1104/pp.65.1.51

Tajima, R., Lee, O. N., Abe, J., Lux, A., & Morita, S. (2007). Nitrogen-Fixing Activity of Root Nodules in Relation to Their Size in Peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.). Plant Production Science, 10(4), 423–429. https://doi.org/10.1626/pps.10.423

Tixier, C., Sancelme, M., Aït-Aïssa, W., P., Bonneymoy, F., Cuer, A., Fruffaut, N., & Veschambre, H. (2002). Biotransformation of phenylurea herbicides by a soil bacterial strain, arthrobacter sp. N2: Structure, ecotoxicity and fate of diuron metabolite with soil fungi. Chemosphere, 46, 519-526. doi:10.1016/S0045-6535(01)00193-X

Zablotowicz, R. M. & Reddy, K. N. (2004). Impact of glyphosate on the Bradyrhizobium japonicum symbiosis with glyphosate-resistant transgenic soybean: a minireview. J. Environ Qual., 33(3), 825-831.